Wages in the Middle Ages

While historians have long appreciated that information on wages and standards of living are among the best evidence to explore the dynamics of preindustrial economies, recent scholarship has pushed wages to the very centre of these debates. Wage evidence has become the fulcrum upon which several grand theories, like the Little and Great Divergences and the Malthusian nature of pre-modern economies, now pivot. Yet, there remains a degree of arbitrariness surrounding both the data and the assumptions that form the basis of the available wage series. For the medieval period, the utility of current series is compromised by small data samples, a narrow focus on certain types of work and workers, and, even where relatively large samples have been used, by inconsistencies in the ways in which the available wage levels have been calculated.

Current controversies concerning wages, earnings, living standards and economic growth are not the product of a lack of source material. Indeed, a main strength of English economic history is the survival of extensive primary evidence. To date, however, these data remain under-utilised and there is an over-reliance upon data gathered more than 50 years ago in a pre-electronic and digital age. By harnessing state-of-the art database technology to traditional skills of Latin and palaeography, this project will gather, analyse and make available the wealth of untapped wage information relating to the employment of men, women and children contained in the many thousands of manorial accounts pertaining to the home farms of manorial lords.

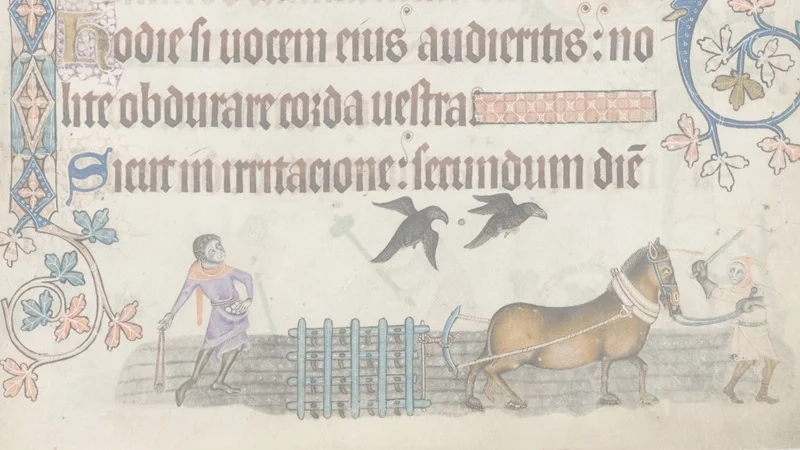

Horse Power: How Medieval England was supplied with equine energy

My work on the medieval horse trade, exemplified by a recent article in Agricultural History Review as well as a monograph in preparation, explores how the English economy was supplied with working horses – its most vital source of kinetic energy – during a particularly important period of England’s (and indeed Europe’s) economic and demographic growth from 1250 to 1350. My book challenges the predominant idea that large institutional landlords produced these animals, and instead illustrates that working horses were supplied by an extensive network of small-scale peasant breeders. This builds upon established narratives of commercialization in medieval England, but argues that this small-scale but widely diffused commercial economy was not characterized by the kinds of capital accumulation typically associated with economic growth.

In medieval England, the breeding of horses was not a major specialism of particular regions nor of certain groups of peasants, but a more generalized activity by individuals who balanced their own needs for animal power with opportunities for breeding and marketing them. The story runs counter to traditional models of economic growth that emphasize capital investment, specialization and aggressive marketing strategies. While the introduction of horses allowed a diversification in activities that expanded peasants’ opportunities for more productive agriculture and increased interaction with markets, a chronic lack of investment meant that there was little progress in terms of stock improvement, technology or marketing which increasingly placed a ceiling on productivity and eventually acted as a drag on levels of commercialization. This is a cautionary tale of unintended consequences that has relevance not only for societies of the preindustrial past but also for many developing economies today.

Milking It: The Entrepreneurialization of the Dairy Industry in Late Medieval England

My examination of the dairy industry looks specifically at how environmental shocks such as the Great Famine of 1315-17 and the Black Death of 1349 as well as new institutional conditions, brought on by the decline of serfdom, led to the shift of a central agricultural industry from the seigniorial sector (landlords and their properties) to the domain of emerging peasant entrepreneurialism. The has significant implications for trends in women’s work and economic agency. By examining the changing composition of labour in the industry, this research informs the debate concerning the English economy after the Black Death and whether it offered women greater economic opportunities than earlier periods; was the so-called ‘golden age of the peasantry’ as beneficial for women as it was for men?